How It Was with Scotland

by Joan Fiset

$16.00

Description

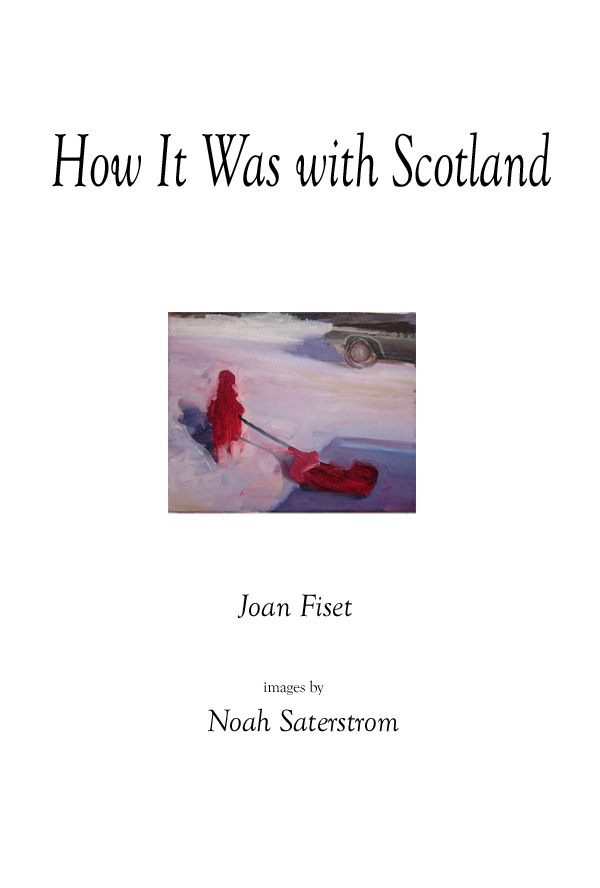

Illustrated with original art by Noah Saterstrom.

This is a book about the presence of absence. Not about, perhaps, but devoted to; loss or absence as our companions, our influences, by whom we are somehow described and known. Read how Joan eloquently discuss this slim and lovely book of poetry and paintings:

When I was six I watched my mother play Emily in Our Town. And somehow I comprehended the acute sense of the life Emily had lost, as she returned to witness the day of her twelfth birthday. Now absent from all life, she could see and fully sense the precious particulars everyone else overlooked as they went about their day. This was my first conscious awareness of the presence of absence. I also encountered it in the late 70s while reading Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room. Jacob died in WWI, but his room contained a palpable sense of his presence. I could feel and almost see him there. Thinking of loss or absence as something to get to know and be known by may seem odd, but this is what informs the poems in How It Was with Scotland.

What made it possible for this relationship to realize itself was my fortunate connection with Noah Saterstrom. Noah’s art in an online journal inspired me to write a poem I sent him. This led to a correspondence and to Noah suggesting we collaborate on a manuscript consisting of his paintings from a box of old famiy photos he’d recently come across matched to poems I d write in response. This process took a year. Noah would send an image created from a photo; I’d write a poem utilizing the image as a catalyst. Because of the back and forth nature of our collaboration I was able to engage in a new relationship to what had been and, at the time, was no more. The literal details of my own experience resonated with Noah’s images in the way of refracted or illumined light making it possible for me to see and comprehend my own story anew. Trauma, I’ve come to believe, is a sacred wood, one to be respected and explored. The pathway through is for each individual to discern. For me language became an ally helping me fathom what, until then, I had been unable to see or fully grasp. Language in concert with Noah’s images gave voice and form to the knowledge and life of loss.

See the fine review in LitPub.

Comments:

“These pictures and words are like overheard whispers or something you almost see from the corner of your eye, or maybe even more intimate than that, like things you are hearing from inside someone’s head before they are words, or memories of things they cannot quite remember. Like secret inside rustlings of longing, hope, regret and quiet beauty.” (Rebecca Brown)

“How It Was with Scotland creates a frisson of ordinary, sensory moments with unthinkable time sequences. Whatever has been named vanishes; whatever has been exiled appears on the next horizon. Fiset’s poetics, comprised of incomplete phrases (words spoken as though overheard, half-recalled, unsayable in entirety), creates a strange sense of our knowing our way around a world that exists truly, yet can’t be found. Reading these poems, memory becomes something that cannot be known or named directly- as it casts itself into lyric and repeats.

Saterstrom’s paintings are the perfect accompaniment to this poetics of incompletion. What we see is instantly recognizable, and even so, each image evokes the invisible, a dimension of the not to be seen-that we fill in as actually there.” (Annie Rogers)

J.D. Ho, writing in The Laurel Review: “How It Was with Scotland (Ravenna Press, 2019) is a hybrid work consisting of poems by Joan Fiset alternating with paintings by Noah Saterstrom. The pairing of words and images is less ekphrasis, and more two forms working together to describe memory and loss. An introductory prose poem, “Outriders,” functions as an epigraph, guiding the reader: In the few lines of prose, two boys sail on a ghost ship, searching for a country they want to name. “When we see it we will know [its name],” one says. All of the poems that follow are untitled, as if the entire collection is a search for this country. Yet our guides are not truly present since they sail a ghost ship, which by definition has no living crew, an apt description of this collection, which reverberates with the lost and the missing and their insubstantial remains.

From the first untitled poem, “…and the late sad weather still becomes,” we occupy a world in which things are missing: context, linguistic structures, perhaps even memories.

space and light

window for the open

you said this is there

you said that will stop

The grammatical structures reveal a consciousness in which much is gone, almost like someone after a stroke or neurological event. This style of grammar recurs, as in the later poem “…a room white breath”:

this night of trees

where flowers lift slowly

sail on as if what

left and

The juxtaposition of something straightforward—an image of trees and flowers—and the sudden break in both location and grammar creates a keen sense of loss or disruption that lies at the heart of the collection. The poems routinely contain erasure, abrupt stops, loss or discontinuation of words, and the sudden taking up of words without introduction or context. Past exists alongside present.

Occasionally, as in “…Small. In morning curious…,” the dreamlike absences in the language hover near contrivance, but then pull back.

Small. In morning curious. An open. Waves will come. This

blue tide remembers.

Shifts like these display how Fiset uses the fragmentary nature of her poems to make resonant connections out of language that might otherwise seem forced. “This / blue tide remembers” grounds and counters the almost coy language of “In morning curious. An open.” The fragments provide incomplete knowledge not necessarily out of an intention to withhold, but because the speaker of the poem simply does not have more knowledge to provide. Many of these poems feel as if their erasures and fragmentary natures recreate the speakers’ experiences, perceptions, and memories.

The paintings that alternate with the poems operate in a similar way: Though they represent entire scenes with houses and people, many of the faces are muted or missing. These are not paintings meant for specificity, but rather association and mood. As with the poems, loss runs through them, both in the sense of loved ones who are gone and in the sense of memories that have faded. Sometimes a poem seems related to the painting that comes before or after it:

here light expands

on a path without breadcrumbs

in the sky no clouds as it ascends

while she waves then turns

only the house

toward a face

first glimpsed

when the search began

is followed by:

Poem and painting share logic, tone, and, seemingly, subject matter. But, at other times, the poems have no concrete relation to the paintings before or after. This may have to do with Fiset’s method of working.

Fiset wrote the poems in Scotland in response to Saterstrom’s paintings. Saterstrom based his paintings on old family photographs. What we experience while consuming this book, then, is several levels of interpretation. Image to image, image to word, word to mind and image to mind. As in a game of telephone, each level of translation and interpretation results in some loss. The poems resemble erasure poems in that much is missing, but what remains may be more powerful than the text in its entirety.

Fiset wrote a number of poems in a previous collection using something called the Private Eye process. This is an activity Fiset uses in writing workshops, often with veterans or children. It involves looking at an object through a hand lens or loupe, which both magnifies and limits your view. Because of the magnification, you see more detail than you would with the naked eye. Because of the limited circumference of the lens, whatever you see is removed from its context. Fiset has students draw what they see in a one-inch square. Then, they enlarge a section of that one-inch drawing, and so on, so that what they see becomes increasingly abstract. Fiset writes that looking at objects through the lens allows her to access emotions that she otherwise could not access. She also notes a feeling of safety with the lens. It is a trusted tool that will not reveal more than the looker can handle.

Whether Fiset employed the Private Eye process in Scotland or not, the poems portray countless levels of loss, distilled through magnification, abstraction, and removal of context. What remains is sometimes decipherable only through visceral response or the reader’s own experience. The purpose of this project seems to be almost the opposite of memoir or confessional. Instead, we look through a poem’s lens for a time, trying to make meaning of what we see.

carnival light calliope

one sugary shard from a windowpane

flickers into view, and from that we must draw a complete picture, pouring our own minds and memories in. We must delve into our own experience and ask: What has been lost?”

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.